Sajid Javid has made it clear that building more homes is his top priority. So what can we expect in his white paper later this month? Recent comments by Gavin Barwell suggest the government is focussed on finding a system that can fund the necessary infrastructure to pave the way for larger scale housebuilding while avoiding conflicts that can make schemes unviable. A housing white paper that finally addressed Britain’s feeble levels of infrastructure investment by tweaking the Land Compensation Act would be transformational.

- It would boost infrastructure investment by £9bn per annum or £180bn over the next 20 years for England alone

- This jump in infrastructure investment would free up new areas of land connected to jobs thereby accelerating housebuilding to the required levels

- By removing the need to speculate on land prices, it would encourage SME builders back into the market bringing much needed competition to housebuilding

- Eliminating section 106 and CIL agreements would allow developers to do what they do best; build houses

- Ensuring that the uplift in land values funds infrastructure would demonstrate that Theresa May’s government truly can make the economy work for everyone and not just the privileged few

The government’s housing white paper, which is expected to be published later this month, is one of the most eagerly awaited pieces of policy of this parliament. Sajid Javid has made his intention clear that driving the delivery of more homes is his number one priority.

In comments to the TCPA New Communities Group last October, the Secretary of State said that land needs to be released in the right places and that the construction market needs to be more diversified with higher levels of SME builders. Critically he has also called for a parliamentary consensus to address this challenge once and for all by taking the necessary radical decisions. Judging by his comments there is every reason to believe that Javid may well be the secretary of state who has the political will to finally resolve Britain’s long-standing housing problem.

Further evidence that the secretary of state is on track came from his housing minister Gavin Barwell speaking at the London property summit in November. Barwell stated that the government is trying to, “find a system that ensures developers pay a contribution from the uplift in value they get from planning permission that helps pay for the vital infrastructure we need to make new housing acceptable, but at the same time avoids conflict and avoids making schemes we want to see go ahead unviable.”

The department’s focus on funding the vital infrastructure permitting greater levels of housebuilding is central to resolving the underlying housing crisis. Indeed, the lack of infrastructure investment in the UK is one of the major reasons why housebuilding rates are so much lower. Infrastructure investment unlocks new land for housing by connecting it to places where there are jobs.

More often than not, identified land for new housing is not sufficiently connected to centres of employment. This reduces the incentive for developers to pursue such opportunities given the demand for housing in these places will be much lower, and therefore the project much riskier. Hence a country with lower levels of infrastructure investment is most likely to have lower rates of housebuilding.

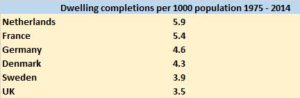

Mckinsey has estimated that the infrastructure stock to GDP of a country is on average around 70%. However, the figure for the UK is substantially lower at only 57% of GDP. As a result, one would expect to see much lower levels of housebuilding rates in the UK. An analysis by the Centre for Progressive Capitalism shows persistently lower rates of housebuilding in the UK compared to other European countries over the last 40 years.

Table 1: Housebuilding rate European comparison 1975 – 2014

Source: Centre for Progressive Capitalism

Germany has an infrastructure stock to GDP of 71% and a considerably higher housebuilding rate. The more important issue for the government to address is therefore why Britain is so poor at building infrastructure as opposed to focussing on developers’ land banks or drawing up policies to subsidise home buyers.

One major factor why the rate of infrastructure investment in the UK is so low is that it tends to be paid for out of general public expenditure. When it comes to prioritising infrastructure against health, education and defence it is not surprising that it has been consistently at the bottom of the list. But financing local infrastructure from general government taxation is the exception rather than the rule internationally. Most of Britain’s competitors across Europe and Asia use land value capture which is a self-financing mechanism for infrastructure investment. This is also one reason why many of these countries have lower budget deficits and yet greater levels of infrastructure stock.

The self-financing mechanism of land value capture works as a result of the new infrastructure supplying the offices and houses to meet the pent-up demand. Once the scheme has been designed, a city region authority generally raises long term finance in the form of bonds from the capital market. The jump in value from the land’s original use value to residential value provides the revenue stream to pay back the bondholders.

The Centre for Progressive Capitalism has developed a land value capture database at the local authority level which permits the assessment of the total potential uplift available to finance infrastructure investment. In Greater London, the value of industrial land is around £2.7m per hectare, however, land with planning permission for residential housing is on average around £26m per hectare. Utilising this mechanism for the proposed Crossrail II project – which aims to unlock 200,000 new houses – would generate an uplift in land values of £69bn. This is more than enough to finance the entire project, and critically without any need for increased net government expenditure.

Land value capture is not just for London though. It can be used all over the country and raise much needed finance for the new Combined Authorities to deliver our necessary 21st century infrastructure. At current housebuilding rates this mechanism could generate more than £14bn of incremental financing for infrastructure in the West Midlands and nearly £14bn for the North West over the next 25 years.

So why has Britain not been using this very effective mechanism to self-finance infrastructure and drive up the rate of housebuilding? The major obstacle is that the 1961 Land Compensation Act guarantees that the uplift in land values, as a result of public infrastructure investment, flows to the landowner instead. This means that landowners generate windfall profits in the region of £9bn per annum for doing nothing. This £9bn is calculated after the various levies from section 106 agreement and the Community Infrastructure Levy (CIL) have been paid – which only amount to just over a fifth of the total uplift. Awarding landowners windfall profits for doing nothing is one of the main reasons why Britain has not been able to self-finance the infrastructure that the country so desperately needs.

This legislation has been long standing and developed out of Britain’s feudal system which supported the rights of landowners over productive activity and capital accumulation. Adam Smith complained in the Wealth of Nations that landowners were withholding land from the market to push prices up, thereby limiting capital accumulation. JS Mill in Principles of Political Economy lamented that the economical progress of a society constituted of landlords, capitalists and labourers, tends to the progressive enrichment of the landlord class. In 1909 Winston Churchill in The People’s Rights thought that rising land values from the productive work of others was unearned income and was therefore unjust.

Clearly this legislation is anachronistic to a modern capitalist system where those who undertake the work ought to be rewarded. Moreover, it is also completely at odds with Theresa May’s view that the economy should work for everyone, and not just the privileged few. Given Mr Javid’s private sector background, it is perfectly feasible that he will be the minister that finally puts an end to the last bastion of feudalism in the UK. A system which has for centuries rewarded the indolent instead of the productive. For Britain, this would indeed a bold step, and one that should be applauded by all parties as a major breakthrough for a more inclusive and successful economy.

It is also a policy that should be applauded by the housebuilders for several reasons. Firstly, there would no longer be any reason to continue to levy the CIL or section 106 agreements which would eliminate viability discussions. Secondly, the industry would be able to focus on a quality price payoff rather than having to overbid for land and then work out how to make the development profitable. Thirdly, the opportunities to build would expand substantially due to the boost to infrastructure investment. Finally, the need to acquire land speculatively, which acts as one of the major barriers to entry for SME housebuilders, would no longer be necessary. City region authorities would either sell land parcels with existing permission and infrastructure in place or they could pursue direct commissioning. Although large housebuilders might initially balk at increased levels of competition, this would allow them to focus on what they do best which is large scale housebuilding and leave the smaller sights to the increasing number of firms who would be able to enter the market.

A housing white paper that finally addressed Britain’s feeble levels of infrastructure investment by tweaking the Land Compensation Act would be transformational indeed. It would:

- Boost infrastructure investment by £180bn over the next 20 years for England alone

- Free up new areas of land connected to jobs thereby accelerating housebuilding to the required levels

- Remove the need to speculate on land prices, thereby encouraging SME builders back into the market bringing much needed competition

- Eliminate the need for section 106 and CIL agreements allowing developers to do what they do best: build houses

- Demonstrate that Theresa May’s government truly can make the economy work for everyone and not just the privileged few