Stop blaming the planning system for everything. Improving the efficiency of the land market will have a far greater effect in driving up the rate of house building than further planning reforms

The government reckons that its housing and planning bill – with the additional measures announced in the autumn statement – will lead to the construction of an extra million homes by the end of this parliament. That means increasing the rate of completions from the 2014 level of 118,000 to well over 200,000 per year. Empirical analysis estimates that there are already over a million plots with planning permission – close to 25 per cent of these in London. And if the current rate of granting permission continues at 250,000 plots per year, this figure will have climbed to over 2 million plots by the end of the parliament. Although there remain some challenges with the planning system, the government must focus on improving the functioning of the land market to drive up construction levels. The way in which volatile and high land values interact with the business model of housebuilding reduces supply. As housebuilders in the UK can profit from rising land values, there is no rational reason why they should ramp up construction. Furthermore, landowners who have been granted planning permission are more likely to hold on to their land for longer before selling it to a house builder to generate incremental profits. Until the government addresses this issue with changes to the 1961 Land Compensation Act, that would allow construction firms to concentrate on the business of building as opposed to balance sheet management, the government’s target is likely to fall well short.

During his autumn statement, George Osborne stated twice “for we are the builders”. Not the greatest of slogans, but his aspirational sentiment is clearly to be welcome given the current bubbly state of the UK housing market. Housing minister, Brandon Lewis said in September that the government has ambitions to build a million homes in England by the end of the parliament. That means increasing the rate of completions from the 2014 level of 118,000 to well over 200,000 per year. It is estimated that England needs to build around 300,000 units a year to meet future demand and to clear the current backlog.

In the autumn statement the chancellor stated that 400,000 of units built in this parliament will be affordable housing starts, backed up a jump in the housing budget to pay house builders for these subsidised units. He also intends to sell £4.5bn worth of government land and property, creating space for more than 160,000 new homes, as well as support for developing brownfield land and new towns.

Osborne conveniently ignored the practicalities of how the construction industry might be able to scale up to achieve these levels, which on its own would preclude the government from hitting the target, and instead decided to focus on his bête noire: the planning system. The chancellor stated that further planning reforms will be brought forward that will ensure delivery against the number of homes set out in local plans by planning authorities.

The planning system, like the perennial public sector IT project has become the butt of endless jokes and a byword for inefficiency. It is much easier for incompetent managers and ministers to lay the blame on something big and clunky that gives the impression that it has a life of its own and cannot be controlled. Without doubt there are some issues with the planning system, particularly the inability of city regions to set their own planning fees to ensure supply meets demand.

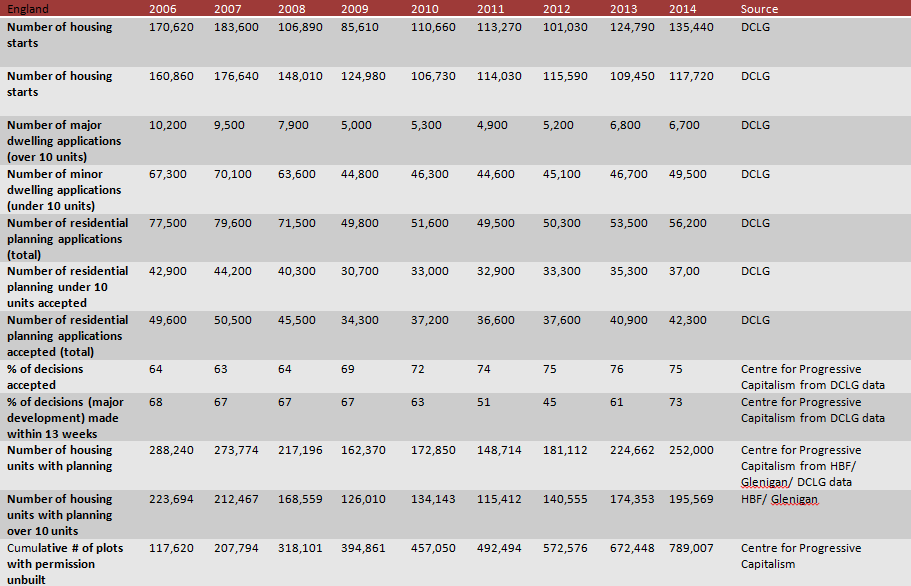

The current regime is still set centrally by the secretary of state, which is rather reminiscent of the approach taken by the Soviet politburo. As a result there is evidence that in areas of high demand for planning there are delays due to insufficient resources. Recent reforms to planning do appear to have had a positive impact on the number of applications that are accepted though. Between 2011 and 2014, 75 per cent of planning permissions were accepted versus only 66 between 2006 and 2010. However, the timeliness of granting permissions has dropped sharply with 66 per cent of applications decided upon within 13 weeks between 2006 and 2010, falling to only 48 per cent between 2011 and 2012. Conveniently the definition for the last two years has been changed to include either “within agreed time frame” or 13 weeks, so it is impossible to tell whether this poor response level has continued due to falling resource levels.

However, the notion that it is the planning system per se that has been the cause of lower rates of construction does not fit the data. Indeed, the lack of empirical analysis when it comes to housing policy is increasingly causing tax payers’ money to be misdirected.

One of the key dynamics of the housing market is that macroeconomic factors have a significant impact on house building. The fall in housing starts in 2008 and 2009 can be attributed to the economic crisis which restricted credit. Lower levels of aggregate demand also resulted in a fall in land values, thus making many projects unprofitable. Since 2010 demand for housing has been robust and credit has been available, resulting in an increasingly pervasive view that it is the planning system that is responsible for lower construction rates. Analysis of the data shows that this view is fundamentally wrong. On average between 2006 and 2014, the planning system has granted permission for 70 per cent more units than have actually been started.

If the planning system were the key constraint then one would expect to see housing start statistics on par with the number of agreed permissions, but clearly this has not been the case. Moreover, this means that since 2006 a large proportion of plots with planning permission has accumulated and not been used. Based on the data compiled, this figure is now close to 800,000 units and continues to rise. If local authorities grant permission for a similar amount of plots in 2015 as they did last year, then England already has over a million plots with planning permission to build on. By the end of this parliament, and based on the current rate of granting permission, there will be 2 million plots with planning permission for construction firms to build on.

Create line charts

Sources: Home Builders Federation / Glenigan / DCLG / Centre for Progressive Capitalism (see notes on the data below)

So why are these plots not being built on at higher rates? This is more likely to be a function of the business model of building houses which is related to the failure of the land market. House builders are required to acquire land at market values – which in many areas is in excess of 200 times those of agricultural values. This generates a lot of volatility in house prices as the economics of house building are sensitive to small changes in demand. Building firms generate excess profits through rising land prices, hence it is not rational for house builders to ramp up house building as it would stabilise land prices. The high price of land also precludes many SMEs from getting involved in building houses thereby reducing competition.

Another factor is that many plots that are granted permission are not owned by construction firms. As landowners are able to profit from the jump in land values from agricultural or brown field to residential land, the longer that supply is constrained the higher their profits. In essence, the way in which the land market currently functions is not conducive to facilitating higher rates of construction.

Hence, if the chancellor really wants to accelerate house building, then he needs to create the conditions for house builders to shift away from depending on rising land prices towards higher productivity as a key success factor. This means that the jump in land prices from agricultural land to residential land would be pocketed by the community to finance the necessary infrastructure including transport, schools and hospitals. Indeed, there is surely a broader debate that needs to take place as to why landowners should be able to pocket the profits of the productive work of firms and workers in their location. The reason for the higher levels of demand for housing is down to those firms and workers, not the landlord.

Where land is publicly owned, rather than selling the land off at market value, public authorities could contract out with construction firms to purely build the units instead. That way firms would be able to get on with the business of building instead of having to worry about financing the acquisition of high-cost land. Public authorities would then sell off the units as per government policy to pay for the construction, but would be able to pocket the jump in land values to fund further infrastructure for the community.

On plots either part or completely owned by private landlords, a tweak to the 1961 Land Compensation Act could be made to ensure that land is sold at values close to use value. This would also ensure that the rewards of productivity flow to the broader community responsible for this progress, and not landlords who happen to own assets in the particular location. Such a reform would also permit construction firms to focus on the business of building rather than ending up as balance sheet managers trying to mitigate the effects of volatile land prices. But until the government decides to look at the data and accept that the planning system is not the main culprit, nothing much is likely to change to the model of house building. As a result, expect the planning system jokes to continue and not much more construction.

Thomas Aubrey is director of the Centre for Progressive Capitalism and founder of Credit Capital Advisory

Notes:

Currently only an analysis between units granted permission above 10 units and housing starts can be directly made. Glenigan provides this data to the HBF. Glenigan has also provided data to DCLG that shows the full amount including permission of sites below 10 units. The addition of these units adds just under 30 per cent more to the figure for sites over 10 units. Using this ratio we have estimated the total figure back in time, which has been triangulated with the number of planning permissions accepted by DCLG for sites less than 10 units. For these estimates to be reasonable, it would require the average number of homes to be built on each site with permission below 10 units to be 1.5, which is a realistic estimate.

Appendix A:

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

[/vc_column_text][/vc_column][/vc_row]

This image is ‘Building site at night’ by Adam Bowie, published under CC BY-NC-SA 2.0