Without a better understanding of the skills mismatches holding back local economies, devolution will not make much difference

‘Too many hairdressers, not enough bricklayers’ is often heard when discussing skills policy in the UK. Like many clichés, things are more complicated. It’s also not hugely constructive if you’re a young person choosing what to do or a college choosing what courses to put on. But it does help stimulate debate on some more important and nuanced issues. Not least, are young people offered good quality technical education and training that is in demand from employers?

Skills is one of the biggest issue for many local economies. It has rightly featured heavily in debates on devolution. For all the talk of giving power away from Whitehall though, up until now not much has changed. But the incoming new metro mayors are set to get control of their slice of the £1.5bn adult education budget soon.

The issue is that local leaders can see the new jobs on their patch but they struggle to get the Whitehall-driven skills system to respond. Whereas university graduates tend to seek employment in fields not directly linked to their field of study, technical education and training is meant to be different. So shaping what is delivered can have a stronger impact on the local economy. If you don’t have enough bricklayers locally, you try to get more people taking courses in bricklaying. That all seems simple enough.

But do we know enough about local skills mismatches in the first place? Debates on the supply and demand for technical skills can all too often lack granular data. This is something that the Centre for Progressive Capitalism has been working with local economies on over the last few months. The Centre is taking advantage of ‘big data’, and is using multiple data sets to triangulate the findings to avoid misreading the trends.

The UK’s most productive sub region

One of the areas we’ve been working with is Thames Valley Berkshire. It is a local economy that is home to almost 900,000 people and half a million jobs, taking in Reading and Slough. They’ve dubbed themselves the ‘UK’s most productive sub region’, owing to productivity per hour worked being higher than elsewhere.

The first thing to point out from our findings though is that there aren’t really too many hairdressers in Thames Valley Berkshire nor is there a shortage of bricklayers. At technician level (the equivalent to A-levels), there were just over two job vacancies for hairdressers for every course completed. So not seemingly too many newly-trained hairdressers. For bricklayers, there weren’t any job vacancies at technician level – so certainly no shortage. But employers were more likely to want candidates at the equivalent to GCSE level, and for these 60 jobs there were just 1.5 vacancies for every course completed at this level.

Myth-busting aside, our initial findings looking across 55 technical occupations are striking. Here are four key points:

- Just one course was completed in ICT for every four job vacancies

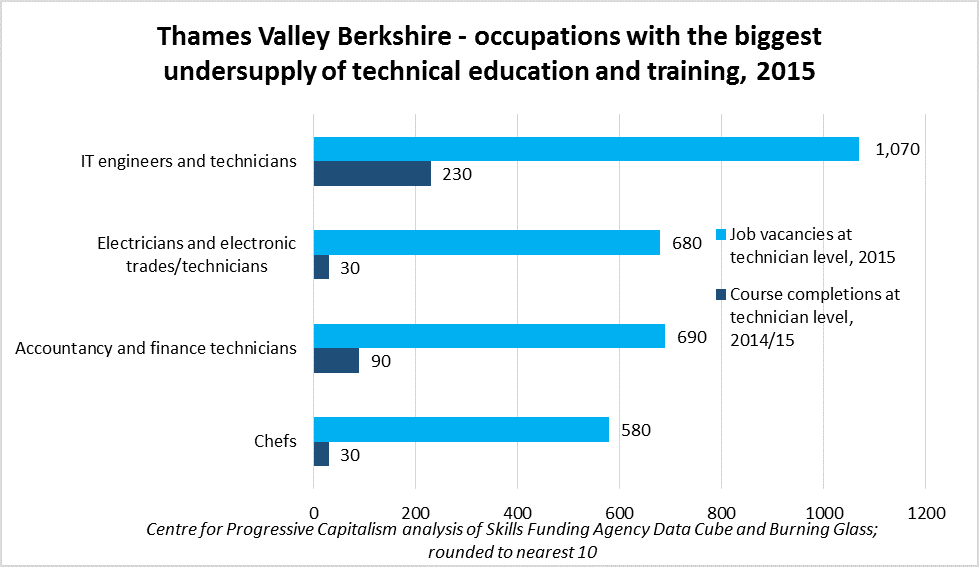

By far the largest undersupply in 2015 was for IT engineers and technicians. There were 1,070 vacancies at technician-level but just 230 course completions.

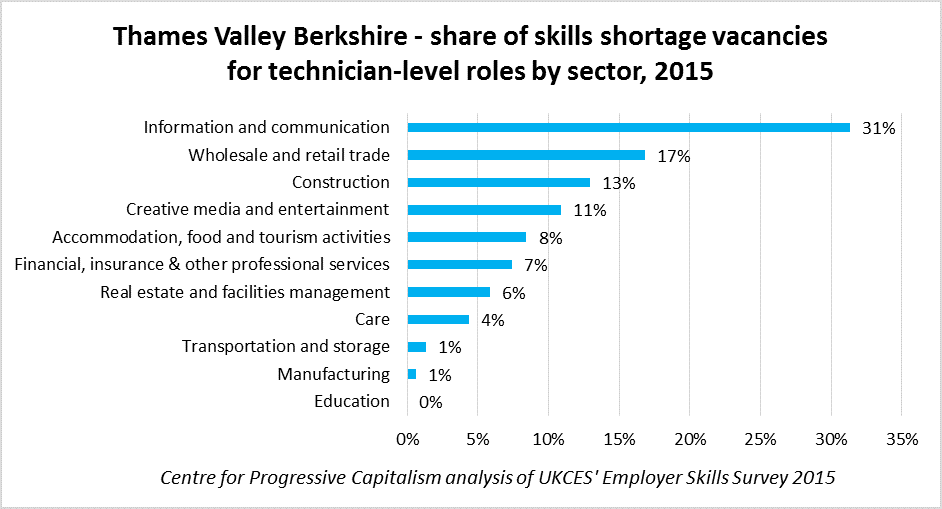

Furthermore, our analysis of survey data drawn from more than 1,000 local employers by UKCES clearly shows that there are major skills shortages in the ICT sector. Of all Thames Valley Berkshire’s ‘skills shortage vacancies’ – those proving difficult to fill due to the establishment not being able to find applicants with the appropriate skills, qualifications or experience – three out of ten were with employers in the ICT sector.

- More electricians, accountants and chefs are needed

There were far fewer course completions in relevant technical courses than job vacancies as electricians, accountants and chefs. These are a diverse range of occupations that could have broad appeal if there was sufficient awareness among young people and adults making decisions about what courses to study. Crucially, this could have a huge impact on their living standards. Some technician-level courses in electrical engineering, for example, add an average of £6,000 to someone’s wages after three years.

- Apprenticeships are just part of the answer

For ICT, it is clear apprenticeships are not plugging the gap caused by a lack of technical education and training in colleges. Despite a major undersupply of college course completions, there were just 60 advanced apprenticeships in 2015. Apprenticeships have dominated political debates and new policy developments on skills for most of the past decade. This is epitomised by the government’s flagship pledge to deliver three million apprenticeships in this parliament. But even with the added incentive of a new apprenticeship levy on larger employers, which is set to be introduced next May, it is hard to see how apprenticeship schemes in ICT could scale quickly enough to plug the gap in Thames Valley Berkshire. So more people need to be taking college-based courses too.

- Hundreds of courses were completed in occupations with few job vacancies locally

There were no technician-level vacancies for artists and designers or public services associate professionals but these had 300 and 190 course completions respectively. There were also just 50 job vacancies for sports and fitness instructors but more than four times as many courses completed. These courses may develop broader skills and help people into employment. But it is hard to argue that some of this provision could not potentially be shifted to ICT and other shortage areas.

Acting on the data

Local policymakers should not be micromanaging delivery in an attempt to have one person doing a course for every vacancy – like some kind of Soviet planning system. Of course, people move between areas. They could become self-employed, so it’s not just advertised job vacancies that matter. And employers could over time switch to recruiting people already in the labour market or recent graduates.

But when there are so many job vacancies in occupations where local employers struggle to recruit it surely makes sense to reform the system to tilt provision towards these shortage occupations. Thames Valley Berkshire’s economy, for example, is dominated by major employers requiring the latest IT skills. These employers should invest in their own training too, including via apprenticeships. But they can also expect a reasonable understanding and aptitude for those they recruit, even for entry-level jobs or apprenticeships. So it matters what local colleges deliver.

This all requires a more granular understanding of how technical education and training interacts with local labour markets. Only then can the local skills mismatch truly be addressed. We might also combat a few more myths.

Alastair Reed is senior policy researcher at the Centre for Progressive Capitalism

The image is ‘Bricks’ by Guilherme Tavares, published under CC BY 2.0