For people’s basic needs to be provided in an era of globalisation, wages need to be rising at faster rates than housing costs. But Britain has continually failed to address its dysfunctional housing market and build sufficient homes

The voters of England have spoken and given a two-fingered salute to Britain’s ruling classes. Disenchanted voters across many former industrial powerhouses including the West Midlands, South Yorkshire and Teesside have made their views abundantly clear by voting for Brexit.

Over the last 40 years, these regions have experienced a dramatic pace of change, driven largely by globalisation. These changes have disrupted people’s work patterns and livelihoods, sometimes generating a catastrophic fall in hope for the future. Many of the industrial jobs that were once based in these regions have moved to lower cost locations, with few good opportunities to replace them. Wage growth has been muted, but the cost of housing has continued to rise.

Recent polling by Populus for the Centre for Progressive Capitalism, however, suggests it is not globalisation per se that is acting as a barrier for the future, but that governments have failed to manage the downsides. Moreover, any retreat from globalisation would itself lead to lower living standards as the pie to be shared between capital and labour shrinks.

An interdependent economy enables countries to specialise in producing goods where they have a comparative advantage. This brings lower prices for consumers, and also creates larger export markets for domestic firms. The greater level of competition spurs greater levels of innovation and therefore higher productivity too, while perhaps most importantly tending to reduce international conflict. But there are negative side effects, and it is these that politicians have failed to deal with.

Crucially, there is increasing evidence that wage growth is less responsive during periods of increased trade openness. This means wages will tend to rise less quickly, despite higher levels of employment. This relationship should not be surprising as numerous economists have argued for some time that a major driver of sluggish wage growth has been greater globalisation, with sectors exposed to greater international competition explaining much of the fall.

As less-skilled workers are displaced, they tend to gain new employment at lower wage levels. In order to maintain profit growth, firms will make decisions to increase labour in regions where their profits are not eroded by wage growth or decide to substitute capital for labour instead.

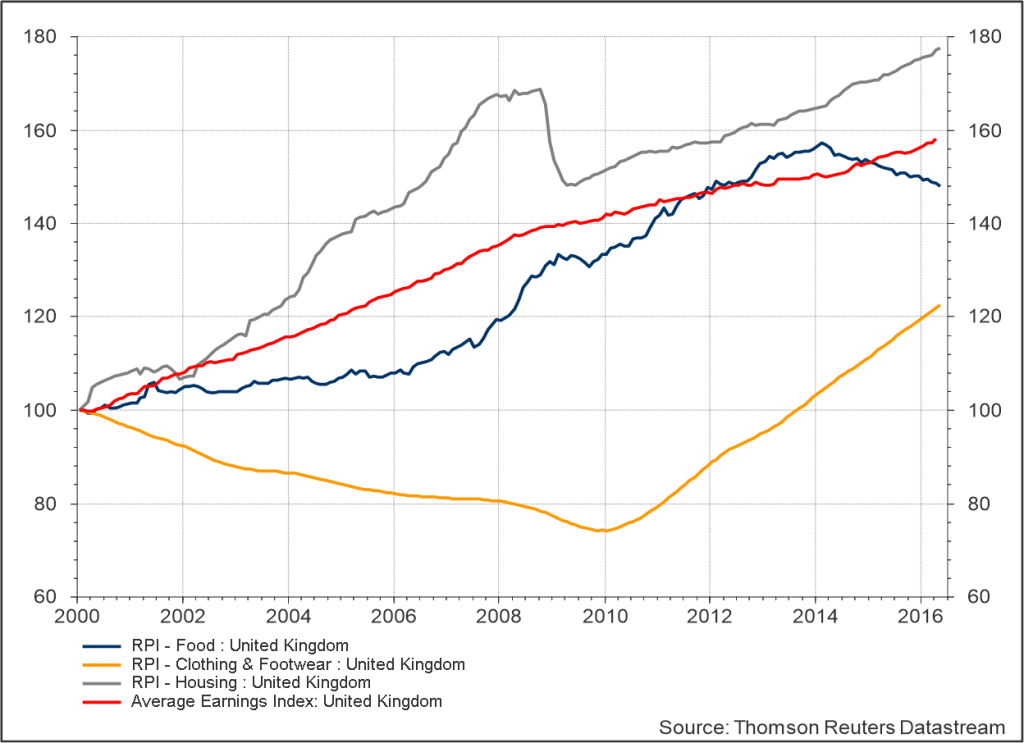

But a lower rate of wage growth doesn’t have to be an issue as long as prices are falling. Far from being the problem, in fact, globalisation can support this through higher productivity. Real wages grow either through higher nominal wages or through falling prices. Our analysis shows that nominal wages have grown faster than both food and clothing since 2000. This is positive as, in terms of these two necessities at least, consumers’ purchasing power has risen.

When set against housing, however, the situation is dismal: housing costs have risen much faster than wages, making workers substantially worse off.

The cost of housing, food, and clothing & footwear vs average earnings in the UK, 2000-Q2 2016 (indexed, 2000=100)

Globalisation has brought many benefits to society, but its downsides have been largely ignored. For people’s basic needs to be provided in an era of globalisation, wages need to be rising at faster rates than housing costs. But Britain has continually failed to address its dysfunctional housing market and build sufficient homes. This is largely down to the inefficient functioning of the land market – which has been compounded in recent years by an increase in global capital flows into land and existing property assets. This combination is an explosive one, and has driven up property prices and housing costs, causing growing anger across many parts of the country.

Brexit must be a wakeup call for those in government to actually address domestic issues such as housing in an era of globalisation. It is of course much easier for politicians to blame someone else for domestic problems than to actually try and fix them. But if these issues are not fixed, as recommended here, the clamour for greater protectionism may well become deafening.

History suggests that any retreat from globalisation only leads to greater political instability and economic insecurity. As the anti-globalisation rhetoric rises in the forthcoming US presidential debate, it needs to be made clearer to voters that a retreat from globalisation is unlikely to solve the major issues impacting many voters. Greater pressure needs to be placed on politicians to manage the downsides instead.

The economist JK Galbraith wrote in 1987 that the “inadequate provision of housing at modest cost can be considered the greatest single default of modern capitalism.” This surely remains the greatest challenge of our age.

Thomas Aubrey is director of the Centre for Progressive Capitalism and founder of Credit Capital Advisory

The image is ‘Brexit’ by Sam, published under CC BY 2.0

Interesting and highly topical given that many commentators assert that the UK, once again, in in the midst of a ‘housing crisis’. It reminds me of the book, ‘Triumph of the City’, a few years back by Harvard academic ‘Ed’ Glaeser. It’s a book I generally was not much impressed by (not least because of its questionable economics). Glaeser did, nonetheless, make one telling observation about the urban regeneration field that I’m familiar with. His finding was what he saw as the biggest strategic error in urban regeneration made by large urban authorities and state governments across the Western economies. That was the mass provision of cheap housing (‘cheap’ in quality and prices to the consumer). He argued that this simply denuded, even destroyed, existing local housing markets and systems. Existing owners and purchasing owners found their properties dropping hugely in value, or even becoming worthless (see Detroit?). For the hapless lower or nil income earning renters they were often entrapped in low quality, badly located, mono-type, managerialy problematic housing run by the local state (see USA projects, France’s banlieues, Scotland’s housing schemes and England’s peripheral estates etc.). There have, of course, been exceptional turn-arounds in that gloomy perspective. Not least is the (unparalleled?) success of the community based housing association movement in Glasgow, Scotland, from the late 1970s onward. That is an example of the role in cities that can be played by socially and economically sustainable model that is: a not-for-profit landlord; managed with an ethos of meaningful and effective engagement with the user community; making judicious use of partial state funding; and subject to rigorous independent regulatory oversight. Where does that model lie in the concept of ‘progressive capitalism’?