Compared to European counterparts, Britain’s housing market is a picture of market failure

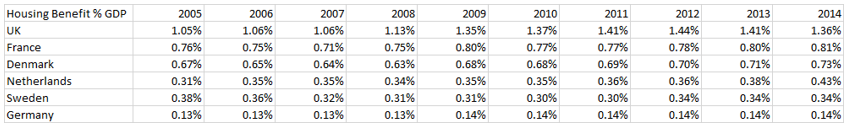

Across the European Union there is often a perception that Britain takes a more market-oriented approach, and where Britain leads continental Europe eventually follows. However, when it comes to housing, this is not the case. Britain’s housing market is far more dysfunctional than its European counterparts. A comparison of two key metrics of a group of six northern European countries demonstrates that the UK has by far the largest market failure in housing. The UK continues to have the lowest construction rate of all six countries. Moreover its housing benefit bill, due to soaring rents, dwarfs that of other countries and is now almost 10 times that of Germany.

No supply

The argument that Britain is not building enough is widely accepted. This is because successive governments have not created the right institutional market infrastructure to permit the supply of houses in growing city regions to keep up with demand. As Mark Carney highlighted in his Mansion House speech this year, without the necessary market infrastructure in place “markets are prone to instability, excess and abuse” – as was amply demonstrated by the Libor scandal. Markets exist to serve society, and when they fail to serve society they need to be reformed.

When compared against other European countries, the UK housing market has the lowest rates of construction in the long run and short run.

Create bar charts

The result of this market failure in the UK has been rising house prices, accompanied by soaring rents. The median house price to earnings ratio for London is now over 10, and for England it is over seven – significantly above historical averages.[2] This not only puts home ownership out of reach for an increasing percentage of the population, but is having a massive impact on renters too. Rent in England is costing 52 per cent[3] of gross disposable income, while the figure for London is estimated by some to be as high as 72 per cent[4] excluding housing benefit.

The extent of this failure can be seen when the housing benefit bills of the six countries analysed are compared. The data shows that the UK redistributes significantly more tax than all other European countries costing Britain a startling 1.4 per cent of GDP – nearly 10 times that of Germany. Attempts to reduce this bill through a benefits cap in 2013 have probably had a small downward effect on the overall amount. However, it is clear that Britain’s broken housing market needs to be fundamentally reformed if construction rates are to jump and the redistribution of taxes for housing benefit due to excessively high rents is to fall.

Market efficiency, not market abuse

Germany’s housing market is far more efficient than Britain’s – requiring minimal government redistribution – simply because the supply of houses is able to keep up with demand. In Britain, one of the major drivers behind the market failure is that it is far more profitable to invest in existing housing assets and land than it is to build new houses. For example, buy-to-let investment has outperformed the UK home construction total return index by over 30 per cent every year since 1996.[5] One other investment strategy that also generates robust returns is to acquire land in dynamic city regions which is subsequently not brought on to the market, thereby restricting the supply of new homes. This in turn drives up house and land prices to even higher levels. It should therefore be of little surprise that 45 per cent of land with planning permission in Greater London is owned by those who have limited intention of developing the plots.[6] Indeed, despite the number of plots with planning permission having doubled in London in the last decade, construction levels have remained flat.

The outperformance of investing in existing property assets as opposed to undertaking actual construction activity is because a large chunk of the rewards of the productive work carried out by millions of firms and workers in dynamic city regions flow to those who own property assets when supply is restricted. This is why in areas of high demand for housing residential land costs around 200 times that of agricultural land in Britain. However, the picture is completely different in continental Europe with residential land acquired at only 10 times agricultural values in the Netherlands and in Germany residential land prices are frozen at use value.[7]

In essence, the market in Germany functions in such a way if that if you have not undertaken the productive work yourself you do not earn anything extra as a landowner, thus emphasising the importance of a productive economy. Britain on the other hand demonstrates that you can earn a lot from other people’s hard work as long as you own property assets, implying the existence of something akin to a rentier economy. In cities like London these rewards flow to landlords, foreign investors and potentially those involved in money laundering who acquire property secretly through off-shore havens. According to Transparency International, one in 10 properties in Westminster are acquired through these shelters, with £120bn of properties across England and Wales registered offshore.[8]

The price at which land is acquired for house building is therefore central to the efficient functioning of the housing market and for stimulating construction and capital investment. Furthermore, the ability to acquire land at lower levels provides the mechanism, through the rise in land prices, to pay for infrastructure which is needed for larger scale housing developments thereby increasing the viability of development projects. This means that the productive work of firms and their workers is rewarded through improved infrastructure such as good quality schools, hospitals, transportation and other local amenities.

Although a significant chunk of land is owned by public authorities, these land plots often do not dovetail with a specific development, thus requiring other land plots to be procured and assembled. The high price of acquiring land can often reduce the viability of the project, particularly if infrastructure is required and needs to be financed. Furthermore, public land cannot be sold out into the market at a discount. But selling land off to the highest bidder often means that this land is then held as an asset with the view to sell at a much higher price later on, rather than being built on.

Adam Smith in the Wealth of Nations attacked the monopoly of land ownership arguing that “the small quantity of land therefore which is brought to market and the high price of what is brought thither prevents a greater number of capitals from being employed.”[9] An efficient market encourages greater capital accumulation by ensuring that construction levels rise to meet the demand for housing. Inefficient housing markets tend to be impacted by local monopoly effects which generate unearned income streams by withholding land from the market resulting in the need for substantial government intervention.

Options and options

A number of housing policy commenters have argued that we need looser planning laws such as the ability to build on green belt land to bring down land prices. Although the ability to build on green belt land will potentially bring more land on to the market, it is also probable that property funds will acquire options on the ugly bits of green belt land that would most likely gain planning permission first. Rational investors would release the land only slowly to keep land prices rising in order to generate significant investment returns for their clients.

Until the UK housing market is reformed and it remains more profitable not to build houses than it is to build them, it is highly unlikely that levels of house building will increase by much. However, should a British chancellor of the exchequer decide to promote a productive economy instead, then all that is needed to be done is to tweak the 1961 Land Compensation Act permitting large scale land assembly by city region authorities to acquire land at closer to use value in conjunction with their own land in dedicated housing zones. This will make the market more efficient, ensure that the rewards of innovation and hard work flow to all firms and workers in a city region rather than to those who own property assets. This would also bring about a greater level of capital investment which Britain so clearly needs.

As George Osborne tours the capitals of Europe proselytising economic reform, he would do well to remember that although Britain does lead in many areas, such as tax incentives for investors in risky companies, when it comes housing, Britain is a picture of market failure par excellence.

Thomas Aubrey is director of the Centre for Progressive Capitalism

Appendix:

Housing construction and benefit data was assembled from individual offices of national statistics from each member state. Nominal GDP sourced from the IMF and population from World Bank and Statistiches Bundesamt.

Notes on data:

The data set for Germany is an estimation based on actual 2004 Wohngeld figures which encapsulated most of the housing payments made to individual households. In 2005 the Hartz reforms meant that social benefits were bundled together making it impossible to split out the portion of benefits specifically for housing. Wohngeld payments are still made but at significantly lower levels with other social benefits making up the difference. A growth rate was applied to the 2004 Wohngeld figure derived from the average compound annual growth rates of Sweden, Netherlands and Denmark.

2014 housing benefit figure for France is an estimate.

[1] France data is for starts. An analysis of the relationship between starts and completions suggests around a 10 per cent difference implying figures of 5.4 and 4.7 for long and short run.

[2] Source: GLA http://data.london.gov.uk/dataset/ratio-house-prices-earnings-borough

[3] Source: English Housing Survey 2013-2014

[4] Tenants in England spend half their pay on rent, Hilary Osborne 16 July 2015

[5] CAGR of UK home construction 1996 2014 is 11.2 per cent pa (Source: Datastream) vs 16.2 per cent pa (Source: Wigglesworth)

[6] Barriers to Housing Delivery, Greater London Authority, December 2012

[7] See http://www.policy-network.net/publications/4810/The-challenge-of-accelerating-UK-housebuilding

[8] http://www.theguardian.com/politics/2015/jul/28/david-cameron-fight-dirty-money-uk-property-market-corruption

[9] Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations Ch IV How the commerce of towns contributed to the improvement of the country

This image is Victorian Houses by Natesh Ramasamy, published under CC BY 2.0